Text

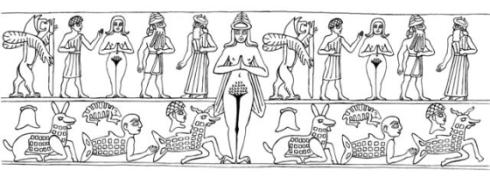

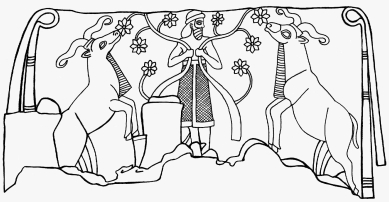

After being completely purified in the netherworld, Inanna is ready to ascend, and at each stage (gate) is dressed with another layer of clothing, thus restoring her original appearance. Therefore, when Inanna/Ištar looses her clothing at each gate she is also deprived of her powers, that is, the soul is on its way to perdition. When, on the other hand, the goddess is given back her clothing, she at the same is restoring her powers, that is, the soul is on its way to salvation. The soul therefore works its way towards heaven along the path depicted later on the Assyrian Tree. Inanna, the defiled soul, was saved, and was able to return to her original state, thus showing the way of salvation for others. In other words, after being “awakened” by “helpers,” she was able to start her gradual ascent from death to living, from impurity to purity. Yet her salvation and resurrection could not occur without a savior, someone to take her place. It is the duty of the good shepherd/king Dumuzi, the husband of Inanna, to play the role of this savior. The sacrifice of Dumuzi explains why the king, a son of a god and thus a god himself, had to die. He was sent to the world to be the perfect man, the shepherd, to set an example for his people to follow and to guide them on the right track. The king, as Dumuzi, died for the redemption of innocent souls, represented by Inanna. But as Inanna/Ištar herself was resurrected from dead, also her savior, Dumuzi the king and the perfect man, was promised resurrection.

The Gnostic savior corresponds to Dumuzi, the savior of the Descent of Ištar to the Netherworld. Just as the Mesopotamian king as Dumuzi was identified as the brother of Inanna, the bridegroom-savior is described as the brother of the Soul in the Gnostic texts. Sophia, the fallen Soul, originally dwelt in the highest heaven together with her Father and Brother. After the fall, her Father sent his son to rescue his daughter from her earthly prison: the redemption occurred through their marriage, the brother becoming the husband of the sister. The sibling relationship of the lovers is also found in Jewish mysticism where Tiferet (the bridegroom) and the Shekhinah (the bride) are called brother and sister, respectively.

The annual death and resurrection of Dumuzi (Tammuz cult) recalls the annually commemorated death and resurrection of Christ, a king and a savior. Although Christians commemorate Christ’s death and resurrection every year, he is not considered as a vegetation god. Similarly, Dumuzi is not just a vegetation god, whose annual death and resurrection only reflected the annual fertility cycle, as is traditionally assumed. The myth of the Descent had a role in the ecstatic cult of Ištar, where the followers of Ištar, i.e., her cult personnel were promised salvation from the material world by following her example set in the Descent. In the Descent, Ištar is saved by the Perfect Man, the king as Dumuzi, who is given as a substitute for the goddess.

Bibliography

| Lapinkivi 2004, 191-194 | Lapinkivi, Pirjo. The Sumerian Sacred Marriage in the Light of Comparative Evidence. State Archives of Assyria Studies 15. Helsinki: The Neo-Assyrian Text Coprus Project 2004. |

| Wolkstein and Kramer 1983, 51, 85 | Wolkstein, Diane, and Samuel Noah Kramer. Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. New York: Harper & Row 1983. |

Pirjo Lapinkivi

URL for this entry: http://www.aakkl.helsinki.fi/melammu/database/gen_html/a0001392.php

|